Emily Moorhead is a kindergarten teacher whose son in grade 1 was exhibiting early signs of dyslexia, a type of learning disability. Even as an elementary school educator, she still felt that she didn’t have the skills to help her child learn how to read. Attempts at home lessons turned into running laps around the yard, and not much progress being made in reading ability. This was when Moorhead drew more of her attention and advocacy efforts to the Ontario Human Rights Commission’s (OHRC) Right to Read report, released in 2019.

The report highlights deficits in Ontario’s reading curriculum and outlines recommendations to remedy poor reading skills that are apparent in many early learners, and not just those with a learning disability. This includes making changes to school curricula, implementing early screening of disability, and changes to university education of future teachers.

Photo by Monica Sedra on Unsplash.

The Right to Read inquiry mentions that the three-cueing method (for teaching how to read) is outdated and perpetuates the false idea that children can learn how to read by simply being exposed to text and literature. The solution to be implemented is to shift entirely to an evidence-based approach known as “structural literacy” – a systematic targeted method that focuses on the building blocks of linking visual letters and words to the sounds they make. This focus on phonemic awareness benefits those with and without a disability to develop foundational literacy skills.

However, a group of academics caution that a complete switch to this systematic method is too narrow. One member, Diane Collier, a professor at Brock University, challenges this so-called “evidence-based” proposal, by asserting that “we don’t have any evidence that this works long-term, … [whether this] makes [for] better readers”. Collier believes that everyone learns in different ways, and a standardized approach could discourage some readers even more. “More research needs to be done on the idea of structural literacy,” as the process of learning how to read cannot ignore the context-dependent nature of reading, in which readers must rely on context and culture to find meaning to words. Thus, Collier believes a moderate approach that blends both structural literacy and “three-cueing” is most appropriate.

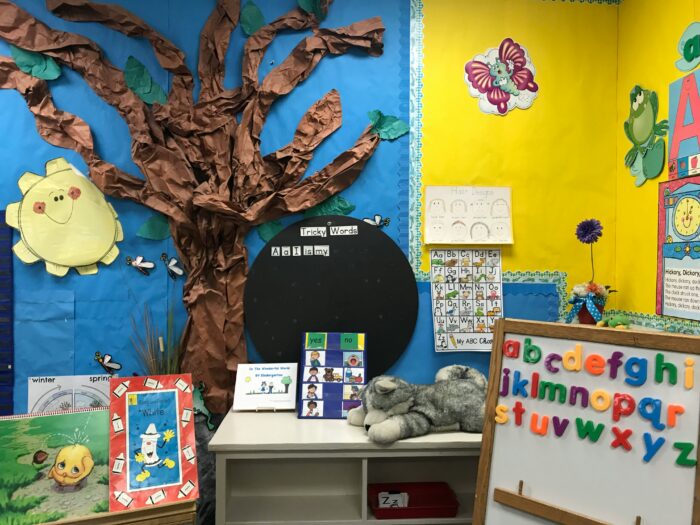

Still, Moorhead remains steadfast. She credits phonics-based learning as the reason for her son’s seemingly rapid ability to read well, after some private tutoring sessions. She has since taken the initiative to educate herself in structural literacy and apply it into her kindergarten reading lessons, even before the OHRC recommendations were rolled out. The students, who are as young as three, can now learn to connect sounds that certain letters make, and rearrange those letters in a way to make a word from all those sounds linked together. Moorhead has called it “code time”, a 15 minute lesson of teaching the rules of letters, sounds, and the simple words that those letters make when combined. Some parents, whose children had Ms. Moorhead as a kindergarten teacher, also praise this strategy, mentioning that “they were keen [and] excited” about reading as a whole.

Tags: language, learning, learning disabilities, neurodivergence, Ontario, primary school, readingCategorised in: Uncategorized

This post was written by Linda H